This was the twelfth in a series of field studies by Dr. Weston A. Price that were published in The Dental Digest during the 1930s. This article appeared in the May 1935 issue (Volume 41, Number 5, pages 161-164). Please see the editor’s note regarding language usage at the end of the article.

* * *

If it is true that the causative factors for the physical degeneration of mankind are practically the same everywhere, it should be possible to find a common cause operating, regardless of climate, race, or environment.

In the studies previously reported1 in The Dental Digest, the groups represented were living in the northern hemisphere and in the temperate or Arctic zones. To extend the variations in nutrition, the field studies in 1934 were made among races chiefly in the South Sea Islands and tropical zones.

The nutrition of the groups previously studied varied widely. For the people in the high Alps in the isolated valleys, it consisted chiefly of rye and dairy products. These native foods were adequate to produce superb physical development with high immunity to dental caries.2 For the isolated Gallic people in the Outer Hebrides the native foods were highly efficient. These were chiefly oats and animal life of the sea.3 For the Eskimos in remote sections of Alaska the local native foods were highly efficient. These were largely limited to products from the animal life of the sea.4 Practically no fruits and grains were available and few vegetables were to be had. For the Indians of the far north and central Canada the foods were found to be almost exclusively limited to the wild animals of the chase, the organs of which were also eaten.5 When these people of various racial stock were studied in their contact with modern civilization (which means a displacement of part of the native foods with imported foods, chiefly white flour and sugar products) there was found to be a rapid lowering of the level of immunity to dental caries and a marked increase in susceptibility to the degenerative diseases. In all succeeding generations a marked increase in susceptibility to tuberculosis was found.

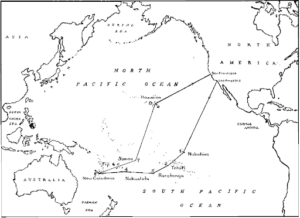

Fig. 1 – Map showing itinerary in South Sea Islands for investigations on nutrition.

In all these groups, among those living on native nutrition not only was there a high immunity to dental caries (usually only a few teeth per thousand teeth examined had ever been attacked by tooth decay) but also there was a marked uniformity of excellence of physical development, including uniform production of the physical characteristics of the race with regularity of development of the dental arches and facial form. At the point of contact with modern civilization and its foods, however, the first and later generations diverged markedly from the normal physical and facial development. Irregularities of the teeth and dental arches and abnormal intermaxillary relationships similar to those found so often among the people of our modern civilizations were frequent occurrences.

It is to be noted that in these groups previously studied each was found to be using liberally either animal tissues or animal products. It occurred to me, therefore, that it would be interesting to find groups that were accomplishing a high efficiency in body building and a high immunity to dental caries on diets that were limited completely to plant foods. The South Sea Islands were selected for this investigation.

We went South through the more easterly archipelagos; namely, the Marquesas Islands, Society Islands, and Cook Islands and then westward to the Tongan Islands in the southern central Pacific near New Zealand and then westward to New Caledonia near Australia. From this group, we went northward to the Fiji Islands, also in the western Pacific; then to the Samoan Islands in the Central Pacific south of the equator, and then to the Hawaiian Islands north of the equator. This itinerary including eight archipelagos is shown in Fig. 1. These islands were populated by different racial stocks speaking different languages.

Through government officials we were able to reach isolated groups, some in mountainous locations far removed from trade or merchant ships.

When the formalities were once accomplished and our wishes made known, the chiefs instructed the members of their tribes to carry out our program for making examinations, recording personal data, making photographs, and collecting samples of foods for chemical analysis.

The photographic work included the making and developing of more than two thousand negatives in the field. It was necessary that the negatives be developed soon after exposure since the high temperature and high humidity reduced the photographic impressions rapidly, approximately 50 per cent in two weeks’ time. This added greatly to the routine difficulties because of the impossibility of obtaining cold water. The night temperature was often over 90 degrees and the daytime often excessively hot and humid.

The food samples were either dried or preserved in solution of formaldehyde.

The detailed records included recording the location, tribe, village and family of every person; his age; previous residence; observations on physical development; the kinds of foods eaten; the physical condition of every tooth; presence or absence of cavities; shape of the dental arches, shape and development of the face, and detailed notes on divergence from racial type. Special physical characteristics were photographed. A comparison was made of these factors for each of the more isolated members of the same tribe and those in the vicinity of the port or landing place of the island. Through the government officials detailed information was secured, usually in the form of the annual government statistical reports showing the kind and quantity of the various ingredients, and articles imported and exported. Whenever possible the health officers were asked to help us in the studies. In many instances the contact with civilization consisted of the call of a small trading ship once or twice a year to gather up the copra or dried coconut, sea shells, and such other products as the natives had accumulated for exchange. Payment for these products was practically always made in trade goods and not in money.

While the missionaries have encouraged the people to adopt habits of modern civilization, in the isolated districts they were not able to depart from their native food because of the infrequent call of the trader ships. In several islands measures had been adopted requiring the covering of the body. This regulation had greatly reduced the primitive practice of coating the surface of the body with coconut oil which had the effect of absorbing the ultraviolet rays, thus preventing injury from the tropical sun. The natives were thereby able to shed the rain which was frequently torrential though of short duration. The irradiation of the coconut oil was considered by the natives to provide an important source of nutrition; whereas wet garments became a serious menace to the wearers’ comfort and health.

The early navigators who visited these South Sea Islands reported the people as being exceedingly strong and generally kindly disposed. There were dense populations on most of the habitable islands. In contrast with this, one now finds that the death rate is often far in excess of the birth rate, so that the very existence of these racial groups is in some localities seriously threatened.

MARQUESAS ISLANDS

The first group studied was the people of the Marquesas Islands which are situated about 4,000 miles due west of Peru. Few if any of the primitive racial stocks of the South Sea Islands were so enthusiastically extolled for their beauty and excellence of physical development by the early navigators. They reported that the Marquesans were vivacious, happy people numbering more than a hundred thousand on the seven principal Islands of this group. A French government official told me that the native population had decreased to less than 5 per cent of the original number, chiefly through the ravages of tuberculosis. Serious epidemics of small pox and measles have at times taken a heavy toll. In a group of approximately one hundred adults and children, I counted ten that were emaciated and coughing with typical signs of tuberculosis. Many were waiting for treatment at a dispensary eight hours before it would be opened. Some of the natives have splendid physiques, fine countenances, and some of the women had beautiful features; but they are a sick and dying primitive group. A trader ship was in port exchanging white flour and sugar for copra. The natives have largely ceased to depend on the sea for food. Tooth decav was rampant in 36.9 per cent of the teeth of the people using trade food in conjunction with the land plants and fruits. There were few natives living entirely on their native foods.

TAHITI

Tahiti is the principal island of the Society group. It is situated 17 degrees south of the equator on the 149th degree of west longitude. Fortunately, degeneration has not been so rapid or so severe here. The population, however, has reduced from more than two hundred thousand as early estimated to a present native population of less than 10 per cent of that number. These islands are a part of French Oceania. Many of the able bodied men were taken to aid France in the World War; only a small percentage returned and they were for the most part crippled. The Tahitians are a buoyant, light hearted race, fully conscious, however, of their rapid decline in numbers and health.

The capital of Tahiti, Papeete, is the administrative center of the French Pacific possessions. It has a large foreign population and there is considerable commerce in and out of this port. A great deal of imported food is used. Just as on the Marquesa Islands, it was difficult to find large numbers of persons living entirely on the native foods. Those that were found had complete immunity to dental caries. Among the natives living partly on trade foods, chiefly white flour, sugar, and canned goods, 31.9 per cent of the teeth were found to be attacked by tooth decay.

RARATONGA

The Cook Islands in the Pacific Ocean are British and under the direct guidance of the New Zealand government. Raratonga is the principal island. It has delightful climate the year round. Racially, according to legend, the Maoria tribe, the native tribe of New Zealand, migrated there from the Cook Islands. In addition to being similar in physical development and appearance, their languages are sufficiently similar so that each can understand the other, even though their separation probably occurred more than a thousand years ago.

Large groups were found in Raratonga living almost entirely on native foods, and it is of interest that only 0.3 per cent of the teeth of these groups have been attacked by dental caries. In the vicinity of Avarua, the principal port, however, the natives were living largely on trade foods and among these 29.5 per cent of the teeth were found to have been attacked by dental caries.

The inhabitants of the three archipelagos, Marquesas, Society, and Cook Islands are Polynesian in origin. Their complexions are tawny but not black. Their hair is straight and their lips are thin. Under British guidance the Cook Islanders have much better health than the Marquesans or the Tahitians. Their population is not seriously decreasing and except for the progressive development of dental disease around the port, they are thrifty and happy and are rapidly developing a local civilization, including a natively supported school system.

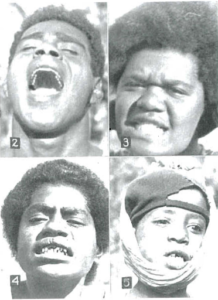

Fig. 2 – A typical Melanesian of New Caledonia and Fiji. Note the splendid development of the teeth and the dental arches. Even the third molars con be seen through the open mouth.

Fig. 3 – A typical Melanesian woman. Both women and the men have superb physical development. Both have great strength and excellent endurance even though their native life is so easy and simple. They are great lovers of sports.

Figs. 4 and 5 – For comparison note the effect of the contact with modern civilization and its foods in such typical cases.

NUKUALOFA

The inhabitants of the Tongan Islands the principal of which is Tongatabu comprise a native population of about 28,000. They have the distinction of being one of the last absolute monarchies of the world. While they are under the protection of Great Britain, they largely manage their own affairs. Their isolation is nearly complete except for a call from an infrequent trader. They seem to be credited by the inhabitants of the other islands as being the greatest warriors of the Pacific. Ethnologically they are said to be a mixture in the past of the darker Melanesians with their kinky hair and the fairer Polynesians with straight hair. It is said they have never been defeated in battle. For centuries they and the Fijian tribes, seven hundred miles to the west, have frequently been at war. The British government has skilfully directed this racial rivalry into athletics. While we were in the Fiji Islands the British government provided a hattle cruiser to carry the football team from Fiji to Nukualofa for the annual contest of strength.

The limited importation of foods to the Tongan Islands because of the infrequent call of merchant or trading ships has required these people to remain largely on their native foods.

The effect of this is shown clearly in the condition of the teeth. The incidence of dental caries of the isolated groups living on native foods was 0.6 per cent; for those around the port living in part on trade foods 33.4 per cent. For a few years following the War while the price of copra was high they traded a considerable quantity for imported foods. The effect of this was clearly to he seen on the teeth of the people who were growing up at that time. Now the trader ships do not call and this forced isolation is clearly a blessing in disguise.

NEW CALEDONIA

The Island of New Caledonia is one of the largest in the Pacific. The New Caledonians are pure Melanesian stock. They are broad shouldered and muscular. These islands are under French control and the foreign population is chiefly French who live mainly in the vicinity of the one port of Noumea. These last three archipelagos, The Cook Islands, Tongan Islands, and New Caledonia are far enough south of the equator to have an equable climate the year round. The subjugation of these people has been difficult and as recently as 1917 a band from the interior in protest to efforts to establish a white colony and sugar plantation on a desirable section of coastal land swept down on the French colony in the night and massacred almost the entire population. Their contact with the required foods from the sea had been cut off. They believe that they need to have seafoods to maintain life and physical efficiency. The physical development of the primitive people and the development of their teeth and dental arches is of a high order. A comparison of the people living near the ports with those living in the isolated inland locations shows marked increase in the incidence of dental caries. For those living almost exclusively on the native foods the incidence of dental caries was only 0.14 per cent; while for those using trade foods, the incidence of dental caries was 26 per cent.

FIJI ISLANDS

The Fiji Islanders are similar in physical development and appearance to the New Caledonians and are also largely, if not wholly, Melanesian in racial origin. They have kinky hair and broad shoulders. They are not as tall as their hereditary enemies the Tongans of the East, and in order to make themselves look equally large they have adopted the practice of training their kinky hair straight out from the head to a height often reaching 6 inches or more. They are British subjects and while they have had splendid assistance they have suffered greatly from degenerative diseases in the districts near the ports and in those in which sugar plantations have been established.

Since Viti Levu, one of the islands of this group, is one of the larger islands in the Pacific Ocean, I had hoped to find on it a district far enough from the sea to make it necessary for the natives to have lived entirely on land foods. Accordingly, with the assistance of the government officials and by using a recently opened government road, I was able to get well into the interior of the island by motor vehicle, and from this point to proceed farther inland on foot with two guides. I was not able, however, to get beyond the piles of shells of sea-forms which had been carried into the interior. My guide told me that it had always been essential for the people of the interior to obtain some food from the sea and that even during the times of most bitter warfare between the Inland or Hill tribes and the Coast tribes those of the interior would bring down during the night choice plant foods from the mountain areas and place them in caches and return the following night and obtain the seafoods that had been placed in those depositories by the shore tribes. Those who carried the food were never molested, not even during active warfare. The guide told me further that they require to have some food from the sea at least every three months even to this day.

Among the sources of animal foods was the wild pig from the bush. These wild pigs are not native but are imported into nearly all the islands and they have become wild where there is an abundance of food for them. Another animal food was coconut crabs which grow to a weight of several pounds. At certain seasons of the year the crabs migrate to the sea in great numbers from the mountains and interior country. They spend about three days in the sea as part of their reproductive program and return over the same course to their mountain habitats. These routes are almost in straight lines. At that season of the year large numbers of them are captured for food. This crab robs the coconut tree of its fruit. It climbs during the darkness and returns before the dawn. They cut off the coconuts and allow them to drop to the ground. When the natives hear coconuts dropping in the night they put a girdle of grass around the tree 15 or 20 feet from the ground and when the crab backs down and touches the grass he thinks he is down to the ground, lets go his hold, and is stunned by the fall. The natives then collect the crabs and put them in a pen and here they are fed on shredded coconut. In two weeks’ time the crabs are so fat they burst their shells. They are then delicious eating. Fresh water is used where available from the mountain streams. Land animal foods, however, are not abundant in the mountainous interior and no places were found where the native plant foods were not supplemented by seafoods.

There has been an extensive development of sugar plantations on the larger islands of several of the Pacific archipelagos. The working of these plantations has required the importation of large numbers of indentured laborers, mostly men. These laborers have been brought chiefly from India and China, and have married native island women. This influx of Asiatics together with that of Europeans has had an important influence on the purity of the native race around the ports. This provided an opportunity to study the effect of intermingling of races on the susceptibility to dental caries. No differences due to ancestry were disclosed by the presence or absence of tooth decay. The incidence of dental caries at the points of contact with imported foods was 30.1 per cent as compared with the more isolated groups who were living on the native foods of land and sea, which was only 0.42 per cent.

Editor’s note: Since the era in which this article was written, society’s understanding of respectful terminology when referring to ethnic and cultural groups has evolved, and some readers may be offended by references to “primitive” people and other out-of-date terminology. However, this article has been archived as a historical document, and so we have chosen to use Price’s exact words in the interest of authenticity. No disrespect to any cultural or ethnic group is intended.

References Cited

- THE DENTAL DIGEST, from March to August, 1933; from February to July except May, 1934.

- Price, W. A.: Why Dental Caries With Modern Civilizations? 1. Field Studies in Primitive Loetschental Valley, Switzerland, DENTAL DIGEST, March, 1933. 2. Field Studies in Primitive Valais (Wallis) Districts, Switzerland, Ibid., April. 3. Field Studies in Modernized St. Moritz, Herisau, Switzerland, Ibid., May.

- Price, W. A.: 4. Field Studies in Primitive and in Modern Outer Hebrides, Scotland, DENTAL DIGEST (June) 1934.

- Price, W. A.: 10. Field Studies Among Primitive and Modernized Eskimos of Alaska, DENTAL DIGEST (June) 1934.

- Price, W. A.: 7. Field Studies of Modernized American Indians in Ontario, Manitoba and New York, DENTAL DIGEST (February) 1934. 8. Field Studies of Modernized Indians in Twenty Communities of the Canadian and Alaskan Pacific Coast, DENTAL DIGEST (March) 1934. 9. Field Studies Among Primitive Indians in Northern Canada, Ibid. (April) 1934.

This is members-only content. Please log in above to access the full PDF.